1. Rearranging the past.

The Museo del Prado in Madrid is completing the rearranging of its pictures, a process established by the Directory Plan for 2009-2012. Following its brilliant policy on online publishing, its website contains an array of videos and features on the topic (general plan, Venetian painting, Flemish painting, 19th century schools, Romanesque and Renaissance, Velázquez – mostly in Spanish). Thanks to the new display, the core of the collection is now placed in the Central Gallery in a way that makes clear the new concept under which the Museo sees itself: not as the typical 19th century encyclopaedic institution with a strict sense of chronology, but the result of the extraordinary taste and determination of the three great collectors-kings of the 16th to 17th centuries – Charles V, Phillip II and Phillip IV. The arrangement becomes therefore a lesson on the history of taste, namely the royal taste, in which Titian was the primary source and Velázquez and Rubens its culmination, displaying a fascinating interplay of influences and innovations that involves other great names from the Spanish, Flemish and Italian (mainly Venetian) schools. It also helps to explain some of the great “holes” from the encyclopaedic and chronological point of view, for instance, Caravaggio and Rembrandt (just one work each) or genre and social painting from the Protestant Netherlands. But there is a second lesson, on political history: this is the centre of a museum that is placed in Madrid, designated capital by Phillip II thanks to its central position, and devoted to a precise role on the European scene, the defence of Catholicism, that explains most of the royal choices.

On the other hand, we can also ask ourselves if this new arrangement does really hide the fact that the Prado is itself a 19th century institution, inaugurated in November 1819. For the rest of the collection (Romanesque to Renaissance, Goya, among others), placed elsewhere in the museum, royal collecting is still important, but the concurrence of other later, less glamorous developments cannot be dismissed. At the end of the day, a vast portion the Prado’s holdings came as a side effect of the mid-19th century “Desamortización” or dismantling of monasteries and other religious institutes, a very anticlerical, liberal and bourgeois political measure. In this sense, I think that the real achievement of the new order in the Prado is not to have found a clear-cut discourse, but to have avoided the aseptic chronological approach, in favour of the richer and more complex fabric of history – in which also the visitor finds himself wrapped up.

2. A video shop for free

The excellent series of videos the Prado is publishing lead to an invitation to join ArtBabble. Although its childish design can be misleading, it is in fact the only video storage web devoted exclusively to the best productions from museums and similar organizations. Founded in 2009 by the Indianapolis Museum of Art, and administered by Robert Stein, Chief Information Officer, the institutions involved are basically the American major ones (Art Institute Chicago, Detroit Institute of Arts, LACMA, MOMA, NG Washington, but not the Met). Only two Dutch museums, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen and the Van Gogh Museum, have been the exceptions until now.

3. “Probably the finest collection in the world”

If you, English reader, can understand the language used here, that is thanks the timely correction work by Rachel Escott – first and foremost a friend, but also the most patient and devoted English teacher I ever had. She is now going an step further, and recommends to all us to have a look to the new website of The Public Catalogue Foundation, a charity devoted “to revealing the entire national collection of oil paintings in public ownership in the United Kingdom”, by means of publishing a picture and a description of every single one of them. Started in 2003 as a catalogue publishing venture, they then realised the potential of the web, and in 2009 convinced the BBC to provide them with a website, named “Your Paintings”. Launched last summer with 60,000 records, it is planned to reach the 200,000 mark at the end of next year. At that time, I will understand if they abandon their Carlsberg-based motto in favour to something similar to “Try to do that in Italy”.

4. A new Velázquez, and an old issue

It seems we are experiencing some years of spectacular rediscoveries, with no less than two (or at least, one sure and one probable) Leonardo’s sleepers being awakened recently. Now a Velázquez is joining the party. The story has been already well publicised: an oil painting, measuring 47 x 39 cm and featuring a gentleman, was consigned to Bonham’s in August 2010 as part of large group of artworks inherited from Matthew Shepperson, a British 19th century artist. At first, it was thought to be worth some hundreds of pounds. But it caught the eye of the auction house’s Old Masters Department, and thanks to further research and the blessing of the specialist Dr. Peter Cherry, it has now a fair chance of being universally accepted as a work by the master. It will be auctioned on 7 December but its estimate, however, reflects some degree of hesitation. It is true that a level of GBP 2,000,000 – 3,000,000 from a previous estimation of GBP 300 is a remarkable leap. But it is also true that “Portrait of a man, called ‘The Pope’s Barber’”, an oil on canvas by Velázquez of similar style and slightly more generous measurements (50,5 x 47 cm), was acquired in 2003 by Spain for €23,000,000 for the benefit of the Prado. On the other hand, for an interesting reflection on why the discussion of this new work will remain so short-sighted in the public domain, read this common-sense brilliancy by the one and only Jonathan Jones at the Guardian.

5. Duchemin The Finder.

For some individuals, identifying Old Masters buried by the past is just their everyday job. Thanks to “Connaissance des Arts”, I came across Hubert Duchemin (1963). Working for Cabinet Turquin in Paris since 2004, and also from his own space from 2010 on, Mr Duchemin has made some outstanding findings. Among the most memorable, three paintings by Jacques Louis David (1748-1825) in 2008, including the oil sketch for his famous “The Death of Marat” (1793), now in the Musée de Bruxelles – for all informations, see Duchemin’s catalogue.

6. V&A first non-Britton head is a proven mastermind.

Martin Roth (Stuttgart 1953), the German new director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, gave this interview to Bloomberg. It is so lightweight, that we must conclude that this is a man better to be known by his acts. In this profile by Artinfo in 2009, some of his constants were made apparent: internationalisation of museums (in his case, collaborations with hot spots like Dubai and China), defence of museum’s identity (in Dresden, that meant spectacular reopening of historical spaces like the Green Vault), a notable gift for running complex organizations (the system in Dresden included 11 institutions) and a commitment for embracing new opportunities (see the brilliant new Albertinium reopened after the 2002 floods). My guess is that we can expect some achievement from this bold appointment.

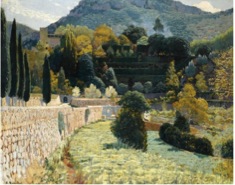

7. Berlin – Barcelona: 1500 km means a long distance also in value

Which of the two above do you prefer? They are painted by near contemporaries Max Lieberman (1847 – 1935) and Santiago Rusiñol (1861 – 1931), probably with just one or two years of difference. In my opinion, choosing one or the other is a question of taste, but not of quality – and for that matter, Rusiñol’s is far bigger, and its brushstroke more conscious. Yet, you can see that there is a huge difference in price. Both are the respective records for the artist in auction for the period from 2005 to today, according to Artnet. But while Lieberman had 95 paintings sold over USD 100,000 (with seven surpassing the million mark), Rusiñol had just 4, and only one in the million zone – this one pictured above. What reason can there be for this? My opinion is that these kinds of paintings are collected locally, and that the German and Jewish communities are certainly stronger in the international art market than the Catalan. Can this change? What do you think?