Una visió internacional per a un art internacional.

Certes limitacions de temps amenaçaven la publicació del post d’aquesta setmana, però la importància potencial de l’únic esdeveniment que tractarem, ens han empès a donar-ne una breu visió, ni que fos ràpida.

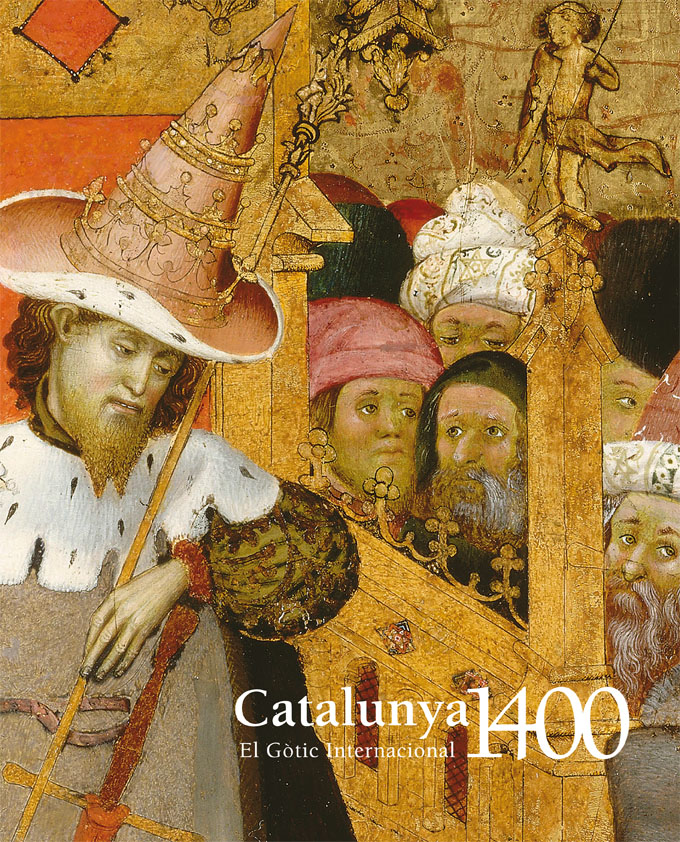

Ahir vam assistir a la inauguració de l’exposició actual al MNAC. El seu títol, senzillament descriptiu, “Catalunya 1400. El Gòtic Internacional” (del 29 de març al 15 de juliol de 2012, entrades per 6 euros i catàleg per 35 euros a la web del museu), dóna immediatament la idea que es tracta d’una mostra sobre la participació catalana en el moviment artístic que es va estendre a l’Europa central i occidental, des de finals del segle XIV fins a l’època de Donatello (1386-1466), Massacio (1401-1428), Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441) i Robert Campin (1375-1444). La denominació que el designa, tal i com recorda el catàleg, va ser donada per l’historiador de l’art francès Louis Courajoud (1841-1896) en una conferència de 1887, publicada al 1901 (Courajod, L. Leçons professées à l’École du Louvre 1887-1896. Vol II: Origines de la Renaissance, Paris 1901; en edició original o imprès per encàrrec a abebooks.com, amb preus de 61,01 dòlars a 616,25 dòlars).

Però per què un tema tan específic de la història de l’art, a sobre limitat geogràficament a aquesta cantonada del Mediterrani pot tenir la seva importància? En primer lloc, per la qualitat de les obres d’art a què va donar fruit. I en segon lloc, perquè mostra com funcionava i com s’ha de tractar ara un fenomen cultural que segueix un camí típicament europeu – el camí que comença amb un naixement com a híbrid de dues fonts principals, segueix amb la seva influència en part de la resta del continent, i acaba per donar lloc a un diàleg creuat, el qual, al seu torn, pot arribar a establir nous centres d’irradiació.

En aquest sentit, l’assaig introductori per part del comissari principal, Dr. Rafael Cornudella, és un exemple perfecte de la visió equilibrada que aquesta mena de qüestions demana. Rebutja tant una aproximació limitadament chauvinista, com una altra, massa indeterminada, que celebrés tots els centres europeus per igual. Per contra, estableix clarament que el gòtic internacional va tenir els seus propis focus principals, a París i la seva zona nord-est i al nord d’Itàlia, que van ser els que van influir la resta dels territoris al centre i a l’oest del continent. És en aquesta perifèria que s’han de situar les obres dels catalans (i també dels txecs, per exemple), tan en termes geogràfics com en termes artístics. Però, tal i com recorda el mateix especialista, un cànon europeu sense aquests exemples perifèrics, seria un cànon molt pobre.

És aquesta la visió que veiem a l’exposició i al catàleg? En part sí i en part no. La selecció de les obres és particularment rica – el número de 48 pot portar a confusió, perquè inclou 5 retaules complets. Els préstecs han arribat d’una ventall variat d’institucions, i algunes de les obres es presenten al públic per primer cop. El catàleg, per la seva banda, toca totes les matèries implicades (pintura, miniatura, escultura, arquitectura) i proposa noves atribucions, sobre la base d’una recerca seriosa i una bibliografia internacional.

Però d’altra banda, la limitació a obres catalanes va en contra de l’esperit de la mostra. El seu missatge s’hauria mostrat amb més plenitud si s’haguessin inclòs alguns exemples de la resta de territoris de la Corona Catalano-Aragonesa (especialment valencians i mallorquins de les darreres dècades de la cronologia considerada), a més d’altres de francesos i italians. Fet i fet, els mateixos artistes que s’inclouen a l’exposició van treballar en aquests àmbits geogràfics.

Està clar que una extensió com aquesta hauria comportat un cost i que les restriccions pressupostàries actuals no permeten grans alegries. Però els organitzadors potser haurien pogut trobar algun altre patrocinador a més de la Fundació Abertis. A més, encara és possible una alternativa ben econòmica: donar entrada lliure a la resta del museu a aquell que presenti un tiquet de la temporal, de manera que el visitant pugui ampliar la seva experiència amb els fons de les sales d’exposició permanent – de fet, proposaríem que l’entrada lliure inclogués també totes les altres institucions catalanes que han deixat peces, donat que els seus números de visites encara necessiten créixer.

Altrament, el MNAC no és responsable per la manca d’una de les peces clau del període. La taula central del retaule de Sant Jordi (c. 1434-35, tempera sobre fusta, 155,6 cm x 91 cm) de Bernat Martorell (1400-1452), que es pot considerar com el cimal de la pintura gòtica catalana, s’ha quedat a les paret de l’Art Institute de Chicago. Simplement han declarat que l’obra com a fora de préstec permanentment. Pel que ens han pogut explicar des de les negociacions, no es tractava d’una qüestió de conservació o de costos de transport. Més aviat estaria relacionada amb les condicions de la donació rebuda pel museu de Chicago. Però resultaria sorprenent constatar que el dret dels Estats Units no proporciona un via per evitar una disposició tan inconvenient. De fet, l’obra de Martorell no ha estat objecte d’una exposició important des de 1939 – només al 2008 es va incloure en una mostra sobre recerca tècnica a la institució mateixa.

Però aquestes limitacions no amaguen el caràcter inspirador de l’exposició, ni tampoc l’autèntic goig que proporciona visitar-la. Gràcies a la seva vocació europea, ajuda a definir la visió que, esperem-ho, se seguirà per a nous projectes – no només en el camp del gòtic. Els seus primers fruits, ja els podem veure aquests dies al MNAC.