An international approach for an international art.

Pressures of time threatened the issuing of this weeks’ dispatch, but the potential significance of the single event I will report this time is pushing me to give, at least, a hurried glimpse of the matter.

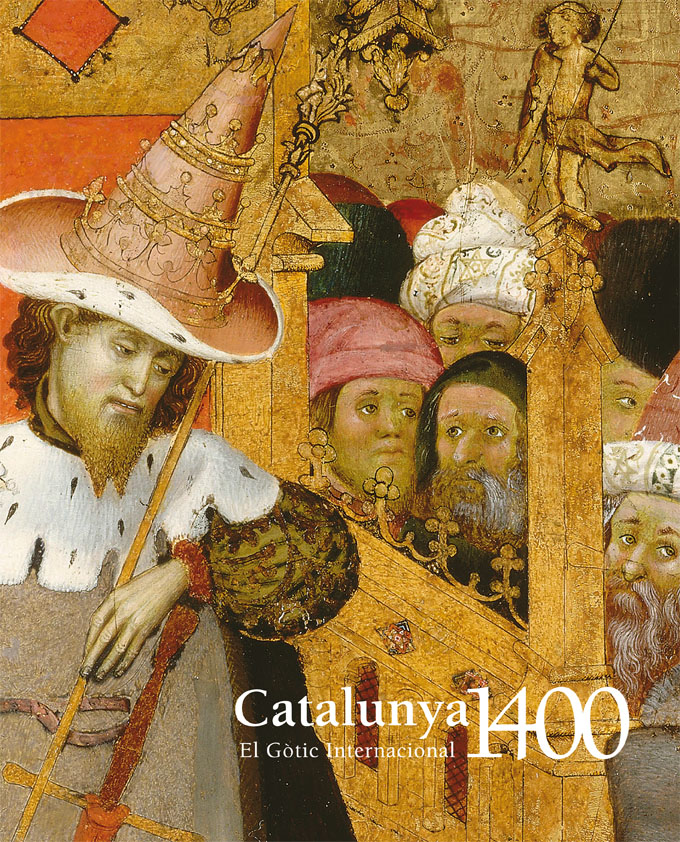

Yesterday evening I attended the opening of the new exhibition in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, in Barcelona. Its title is the plainly descriptive “Catalunya 1400. El Gòtic Internacional” (“Catalonia 1400. The International Gothic Style”, from 29 March to 15 July 2012, admissions €6, catalogue for €35 at the museum’s website), which gives you the immediate idea that it deals with the Catalan part in the art movement that spread over central and Western Europe, from the late 14th century until the age of Donatello (1386-1466), Massacio (1401-1428), Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441), and Robert Campin (1375-1444). The term that it names, as the catalogue of the exhibition remembers, was coined by the French art-historian Louis Courajoud (1841-1896) in a conference in 1887, published in 1901 (Courajod, L. Leçons professées à l’École du Louvre 1887-1896. Vol II: Origines de la Renaissance, Paris 1901; the original issue or printed-on-demand at abebooks.com, with prices ranging from $61.01 to $616.25).

But why is such a specific subject of art history, geographically narrowed to this corner of the Mediterranean Sea, of some importance? First of all, because of the quality of the works involved. And secondly, because it shows how to deal with a typical pattern for European cultural phenomena – a pattern that starts with being born out from the hybridization of two different main sources, then impacting on some territories of the rest of the continent, and finally giving way to general cross-dialogue, which, in some instances, establishes even new centres of irradiation.

In this respect, the introductory essay by the chief curator of the exhibition, Dr. Rafael Cornudella, is a perfect example of the balanced view the issue asks for. He rejects both a chauvinistic approach and a pan-European all-inclusive celebration, and clearly states that International Gothic had its own principal focus, in Paris and its North-East area, and in Northern-Italy, which influenced the rest of the central and western part of the continent. It is in this periphery where the Catalan or for this matter, the Bohemian – Prague examples lay, both in geographical and artistic terms. But, as Dr. Cornudella says, a European canon without them would be unforgivably poor.

Do we see this in the exhibition and its catalogue? In part yes, but in part no. The selection of the works is certainly rich – the number of 48 can be misleading, since it includes 5 complete altarpieces. Loans come from a variety of institutions and some works are presented to the public for the first time. The job behind it should be Herculean. In the same vein, the catalogue touches all the disciplines involved (painting, miniature, sculpture, architecture), and comes up with some new attributions, based on serious research and an international bibliography.

But on the other hand, the “only Catalan works” restriction put on the show works against its spirit. Its message would be fully revealed with some works from the rest of the Catalan – Aragonese territories (especially Valencia and Mallorca from the last decades of the chronology span), and with some examples from the French and Italian workshops of the moment. Not least, the artists themselves worked occasionally for all these territories.

It is clear however that such an expansion would come at a cost, and that the current budget limitations do not allow for big dreams. But perhaps the exhibition organisers could find more supporters than just the one, the Fundació Abertis. And there is a cheap alternative still available: to give free entry to the rest of the museum to exhibition’s ticket holders, so they could continue their experience by exploring further examples from the museum’s collection – I think that extending free admission to all of the Catalan institutions contributing to the exhibition could also be a clever marketing move, since their attendance numbers are not robust.

The MNAC was not to blame for the absence of a certain crucial work. The central panel of the Saint George altarpiece (c. 1434-35, tempera on panel, 155.6 cm x 91 cm) by Bernat Martorell (1400-1452), which is arguably the crest of the Catalan art of this moment, remained on the walls of the Art Institute of Chicago. They simply declared the work as permanently out of loan. Asking people engaged with the corresponding negotiations, the answer was that this was not a conservation, nor a shipping cost issue. It seems it could be related to the terms of the gift to the Chicagoan museum. But I would be surprised to learn that the American legal corpus and genius does not offer or find any means to get around such an ill-conceived provision, should it have been actually put in place. As a matter of fact, the work has not been included in any important exhibition since 1939 – the only instance was in 2008, but in a show focusing on in-house technical research.

But these shortcomings do not hide the inspirational value of this exhibition, and do not harm the real joy of coming and seeing it. Thanks to its European vocation, the show cleverly embodies a vision that hopefully will shape further, exciting developments, not only in the Gothic area – and it actually unveils its first promising fruits.