1. Restitution: a very short introduction.

Since the first points of today’s post deal with restitution, I feel it is worth starting with a brief note about the origins of its most famous and common cases, those related to Nazi looting of Jewish properties between 1933 and 1945. The current situation is born out of an international legal framework that, as you probably already know, has its foundation in the 1998’ Washington Conference On Holocaust-Era Assets, at the end of which the 44 national delegations present adopted the Washington Principles (you will find them in the Appendix, p. 971, of the Proceedings of the Conference). Ordering a direct and automatic mandate for restitution would have been too controversial due to the different legal systems involved, each of which sets its own rules in a key point: the deadlines and conditions for filing the corresponding claim (technically called “statute of limitations” or “period of prescription”). Instead, the delegates at the Conference adopted a more pre-litigation approach, and committed themselves to identify “art that had been confiscated by the Nazis” (principle 1) and to find a “just and fair solution” (principles 9 and 10) for the surviving heirs. There was therefore ample room for research and negotiation (but also for eventual litigation), and although different states and museums had set up their own bodies of investigation, it has been two private organizations, one in the US (Commission for Art Recovery, founded in 1997) and another in Europe (Commission for Looted Art in Europe, founded in 1999) who have taken the lead for the cases involving particular claims. Thanks to their hard work, the outstanding quality and value of the art works involved and the central position the Holocaust occupies in the European and American public conscienceness, the cases have made headlines on more than one occasion – see The New York Times’ feature “Art Restitution News” in its website’s topics.

2. “Talk!”, said the American judge

But, what happens when the case is not a Holocaust-related one, and therefore lacks the legal framework detailed above? Quite simply, it is treated as just another robbery case, and approaches and results can vary. In this long article in the Los Angeles Times, you will find a recap of the case confronting the Armenian Apostolic Church of America and the Getty Museum. The dispute is over the opening leaves of a book of Gospels called the Zeyt’un Gospels, bought by the Getty in the US in 1994, but removed and robbed from the original work in 1916, in the wake of Armenians’ expulsion and killing from the region of Cilicia (now belonging to Turkey), by the Turkish army. The Getty wanted the claim to be dismissed on the grounds of California’s statute of limitations, which asks the rightful owner to file its claim in within 6 years of being made aware of the location of the work. However, the judge, quite sensitively, decided not to grant Getty’s petition and ordered mediation instead. We will see how it ends.

3. “Mine!”, said the French State

“Shocked!” was the reaction of London’s Jermyn’s Street dealer Mark Weiss, when last 8th November he learned that the French Ministry had placed an export ban on Nicholas Tournier’s (1590-1639) “Carrying of the Cross” (oil on canvas, 220 x 121 cm, c. 1628 – 1638) he was exhibiting in his stand in the recently closed Paris Tableau fair. According to the different reports published (listed below), the work of art had a colourful history. Commissioned in 1630 for the church of the Pénitents Noirs in Toulouse, it stayed there until pillaged by revolutionaries in 1794. Some time later it was offered to the Musée des Augustins in the same city, from where it disappeared (for a still undetermined reason) in 1818. The passing of time buried it until it resurfaced in Florence in 2009, but labelled just as a “Follower of Caravaggio” work, in Sotheby’s sale from the estate of Salvatore Romano (1875 – 1955), a noted Florentine art dealer. It was bought there for €57,500 by Hervé Aaron, a Paris-based leading art dealer, who identified the work as the lost one from the Toulouse museum. He informed the director of the Musée des Augustins, Mr Axel Hémery, about it – himself a Tournier expert (he organised a retrospective of Tournier’s work in 2001). Despite a note about the painting and its loss being included in some obscure part of the already 8 year-old exhibition catalogue, Mr Hémery did not believe in the connection and declined the purchase. Subsequently, Aaron included the painting in his stand at the 2010 TEFAF fair in Maastricht, with a price tag of around €400,000. This fair is the most important for Old Masters, and the Art Loss Register is in charge of vetting it. However, the painting passed ALR test, probably because nobody has ever filed a claim about it in the organisations’ database. At the fair, the painting caught the eye of Mark Weiss, who acquired it, and immediately reoffered it to the museum. But Hémery was not still sure about the Augustin provenance. In the last TEFAF 2011, Weiss hung the painting on his stand, clearly stating the Augustin origins and asking €657,000, although ready to offer a discount to the Museum, with whom he was engaged in ongoing negotiations. As part of them, and since the director of the museum had been finally convinced of the existing relationship, Weiss made the most natural move, which however revealed itself to be quite a error: to bring the painting back to France, as part of his booth in the Paris fair. It was sooner rather than later that Mr Weiss received an official note form the Ministry stating that the work, which they considered as stolen from the Augustins, was therefore blocked for export. The grounds for that decision were that, according to French law, works of art from French museums are “inalienable and imprescriptible”, meaning not only that de-accessioning is nearly impossible, but also that in case of unclarified disappearance, the work remains the property of the museum whatsoever the lapse of time is (no statute of limitations there). Mr Weiss found himself suddenly stripped of his ownership title, and left with little prospect of selling the work, since it is the policy of the French authorities “not to buy what the State already owns”. Last reports, however, indicate that the Ministry and Weiss are about to reach an amicable agreement: the painting is now under the care of the Ministry’s Direction Générale des Patrimoines, and Mr Weiss has received a letter from the Ministry offering to negotiate not a price, but a fair compensation. It is precisely this happy end, and the insistence by Mr Weiss that he has been always willing to see the painting back in the Augustins, that places a big question mark over the agressive move from the French Ministry: was it really needed? In my view, its immediate effect is to discourage the reporting to French institutions about any other new finding.

Reports used for this note include:

Didier Rykner, “Imbroglio autour d’un Portement de Croix par Nicolas Tournier”, La Tribune de l’Art, 7th November 2011, as consulted in www.latribunedelart.com in 14th November 2011;

Scott Sayre, “200 years later, France claims a missing artwork”, NYT Arts Beat blog, 8th November 2011, as consulted in http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com in 14th November 2011;

Tom Flynn, “Art Loss Register defends its Due Diligence vetting at TEFAF”, Artknows, 9th November 2011, as consulted in http://tom-flynn.blogspot.com in 14th November 2011;

John Lichfield, “France bars removal of ‘stolen’ masterpiece”, The Independent, 10th November 2011, as consulted in www.independent.co.uk in 14th November 2011;

John Lichfield, “Gallery returns France ‘stolen’ masterpiece”, The Independent, 10th November 2011, as consulted in www.independent.co.uk in 14th November 2011;

Anonymous, “Le propriétaire du tableau de Nicolas Tournier conteste l’interdiction de sortie de territoire demandée par la France”, Artclair.com, 10th November 2011, as consulted in www.artclair.com in 14th November 2011.

4. And then came the Walloons.

As reported by Artclair.com, last 8th November the Parliament of the Fédération Wallonie – Bruxelles has adopted a resolution claiming Rubens’ magnificent “Triumph of Judas Maccabeus” (oil on canvas, 310,8 x 228,5 cm, dated 1635) from the Musée des Beaux – Arts in Nantes, France. The work was commissioned by the bishop of Tournai for the cathedral along with “The Issue of Souls in Purgatory” (also by Rubens, same measurements and date). Both were plundered by revolutionary French troops in 1794, the second one was returned to Tournai, via Ghent, in 1816, but the first one remained in France. It seems the Walloon parliament has chosen the diplomatic way, rather than pleading in courts. In this respect it follows the federal (all-Belgium) policy of not claiming works disappeared from the national territory before 1830, the date of the foundation of the Belgian State. The interesting reasoning behind this practice is that previous to this date, no works could be considered as staying in the Belgian State territory, because that state did not exist at that moment.

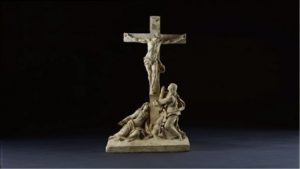

5. Clodion in Oxford

The Ashmolean Museum has purchased an important work by Claude Michel (1738-1814) known as Clodion, one of the most accomplished sculptors of 18th-century France. A favourite of the Ancien Régime’s upper classes thanks to his extremely graceful little terracottas, executed with ultimate craftsmanship and featuring light mythological subjects with satyrs and nymphs, Clodion also showed aptitude for more profound matters, as this singular Crucifixion (terracotta, 70 cm, dated 1785) shows. The catalogue of the great retrospective in the Louvre in 1992 confirms this (Poulet, Anne L., Scherf, Guilhem: Clodion 1738 – 1814, Paris, 1992, 489 pp., difficult to find). The work has the rare quality of showing deep feeling without falling into desperation, and despite its generous measurements, it retains Clodion’s ability in creating groups arranged with an elegant cadence. It was created as a model for the Great Rood surmounting the new choir screen in Rouen Cathedral, commissioned from Clodion and other leading sculptors in 1771. The screen was dismantled in 1884 and bombing in 1944 damaged the final sculpture; the model becoming therefore the last evidence of the large commission. Sold in 1996 in Sotheby’s London for GBP 52,100 (including premium, according to Artnet), and on loan to the Ashmolean since 2003, it has been now bought for GBP 242,262, with the support among others of a GBP 120,000 grant from the Art Fund – see the Art Fund press note.

6. Joli in Madrid

Thanks to the generosity of the International Patrons of the Fundación de Amigos del Museo del Prado (Prado Friend’s Foundation), Antonio Joli’s (1700-1777) “Visit of Queen Amalia of Sajonia to Trajan’s Arch in Benevento” (oil on canvas, 77.5 x 131 cm, c. 1759) has entered the collections of the Museum. To celebrate the acquisition, the Prado is organizing a small exhibition around the work (from 10th November 2011 to 26th February 2012, in room 21), while the Fundación Amigos del Prado has published a complete study of it, available online. In it, Dr. Gudrun Maurer argues that the painting shows Joli as responding to the then innovative study of archaeological remains. In this sense, both the exhibition and the study work as a perfect complement to the current exhibition in the neighbouring Thyssen Museum, called “Arquitecturas pintadas” (“Painted Architectures”, from 18th October to 22nd January 2012, admission €8). With more than 140 works coming from different museums around the world, it charts the rising of the representation of architecture from a simple element of the composition to a genre in itself. It groups the major names in the field, from medieval Duccio di Buonsegna (1278-1319) to late 18th century Hubert Robert (1733-1808), including 6 works of Joli that record his activity not only as a landscaper of ruins, but also as a Madrid city life portraitist (see the exhibitions microsite with the complete list of works exhibited).

7. And Miró at home.

Although not belonging to Old Master’s matters (yet), I cannot help commenting on Miró’s retrospective as installed in the Fundació Miró, Barcelona (“Joan Miró, l’Escala de l’evasió” from 16th October 2010 to 18th March 2011, tickets €10, exchangeable for a year-long membership). Having seen it in Tate Modern, I would say the difference is that in London Miró’s works were treated as important guests, but in Barcelona they are plainly at home. It is easy to realise that the trees, the soil, the sky and the very colours you see outside are those that Miró brings out in his paintings, setting them on a path of transformation that leads to unexpected territories. Memorable moments include the three triptych rooms, each piece installed on one of the three perpendicular walls, so you can sit surrounded by them; and the staircase grand room, in which the “burnt” paintings that hang 6 metres high as if flames were taking them up, can however be approached thanks to the ascending stairs that run attached to the walls. On the negative side, we can only note a somehow muted lighting in the opening rooms.

In short, an excellent occasion to come to the Fundació. And don’t leave your young ones behind. Since its early days, the Fundació has offered an excellent children’s programme, from October to May, especially good in puppets. A perfect excuse to follow’s Rachel Escott’s advise of “getting them early”, in this post of her “Communicating the Arts” blog, in which she echoes the findings of an official survey.