1. Back to work.

I am reviewing these notes, which I wrote some days ago for this week’s post, after six days of extraordinary events in my city and my country. One of the attacks’ objectives was to break up our way of life, and it would be too easy to pretend nothing has changed. But, even if they have hit hard, some good is coming out of it, thanks to the stubborn and generous efforts of so many. We are healing the wound, and perhaps these notes, which are business as usual, are not out of place.

2. MNAC’s list.

I just realized an interesting fact. In 2009 the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya celebrated its 75th anniversary with an exhibition called Guests of Honour, bringing into the museum a group of fine works the museum wished were in its collection. For most of them this was just impossible, since they were already in other museums. For others, still in private hands, there was still hope, and in fact, today two of them are hanging in its walls: The Darcawi Holy Man of Marrakesh, a watercolour by Josep Tapiró acquired in 2013, and Pere Serra’s Crucifixion of Sant Peter (c. 1400, tempera on wood), which was part of the Gallardo donation of 2015.

3. Fidel Aguilar (1894-1917).

One of the works in the MNAC’s exhibition was this Head by Fidel Aguilar of 1916, now in a private collection. It has been exhibited again, until two weeks ago, in the retrospective, short (Aguilar died with only 22 years) but very comprehensive, in the Casa Pastor of Girona (A Shooting Star: Fidel Aguilar (1894-1917). Its fine catalogue is by Eva Vàzquez and Jordi Falgàs. In both the central essay of the book and the central room of the exhibition they draw parallels between the works of Aguilar and his friend Enric Casanova, on the basis of their common influence by Archaic Greece’s sculpture – they were following the trend set by Aristides Maillol some years (as seen in the Maillol and Greece exhibition in the Museu Marés in Barcelona last year).

4. Enric Casanovas (1882-1948).

After Aguilar’s, perhaps it is time for a Casanovas’s retrospective – the last one was in 1984 in Barcelona, with Teresa Camps as its curator and writer of its catalogue. In 2008, Susanna Portell presented Enric Casanovas: escultor i amic, (“Enric Casanovas, and sculptor and a friend”) in the Fontana d’Or in Girona, which focused in his relationships with other artists. More recently, both Camps and Portell edited Les cartes de l’escultor Enric Casanovas (“The Letters of Enric Casanovas, Sculptor”, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2015).

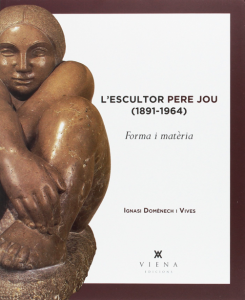

5. Pere Jou (1891-1964).

A member of Aguilar’s and Casanova’s generation, Pere Jou has also received his share of research recently. Last year, Ignasi Domènech published his PhD dissertation, which is a biography and catalogue raisonné of his work: L’escultor Pere Jou, 1981-1964. Forma i matèria, (“The Sculptor Pere Jou, 1891-1964. Form and matter”, 2016, 334 pàgs; the original of the dissertation here.

6. Freedom works.

The reform of the Italian museums introduced two years ago, which gave them more autonomy and new directors (some of them foreigners), continues to deliver. Minister Franceschini proudly announced a global increase of 7% in visitors for the first half of 2017, reaching a record 50 million – Il Giornale de l’Arte features the case of the Galleria Borghese, which introduced a new ticketing system. Furthermore, Franceschini’s policy of allowing hiring non Italian directors has been recently uphold by the State Council, the highest administrative court in Italy, in the case over the Colosseum’s administration brought by the Major of Rome (more at Il Fatto Quotidiano).

7.The Zugaza’s factor.

Miguel Zugaza is performing as his best in his second round as director of the Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao. Their current exhibition, of the excellent collection of Alicia Koplowitz (until October 23th) is an enlarged version of the one showed in the Jacquemart-André in Paris. His is also talking about an expansion of the museum (article at El País).